Further details on monetary policy

Loanable funds and changes to the interest rate

When explaining monetary policy on the Monetary policy 1 and Monetary policy 2 pages, we are treating changes to (1) the supply of loanable funds, (2) interest rates, and (3) borrowing (i.e., actual loans) as all happening at the same time. It’s useful, however, to understand that each one causes the next.

First, we should clarify that we are actually interested in the market for loanable funds, not the loanable funds provided by a single bank. There will numerous banks in a region (or even a country) that can all supply loanable funds to firms and consumers. Using just one bank in our analysis, however, makes it easier to understand these processes that affect aggregate demand.

Next, as we have said, when the reserve requirement decreases, the supply of loanable funds will increase. This is simply a matter of banks suddenly having more in reserve than they are required to have.

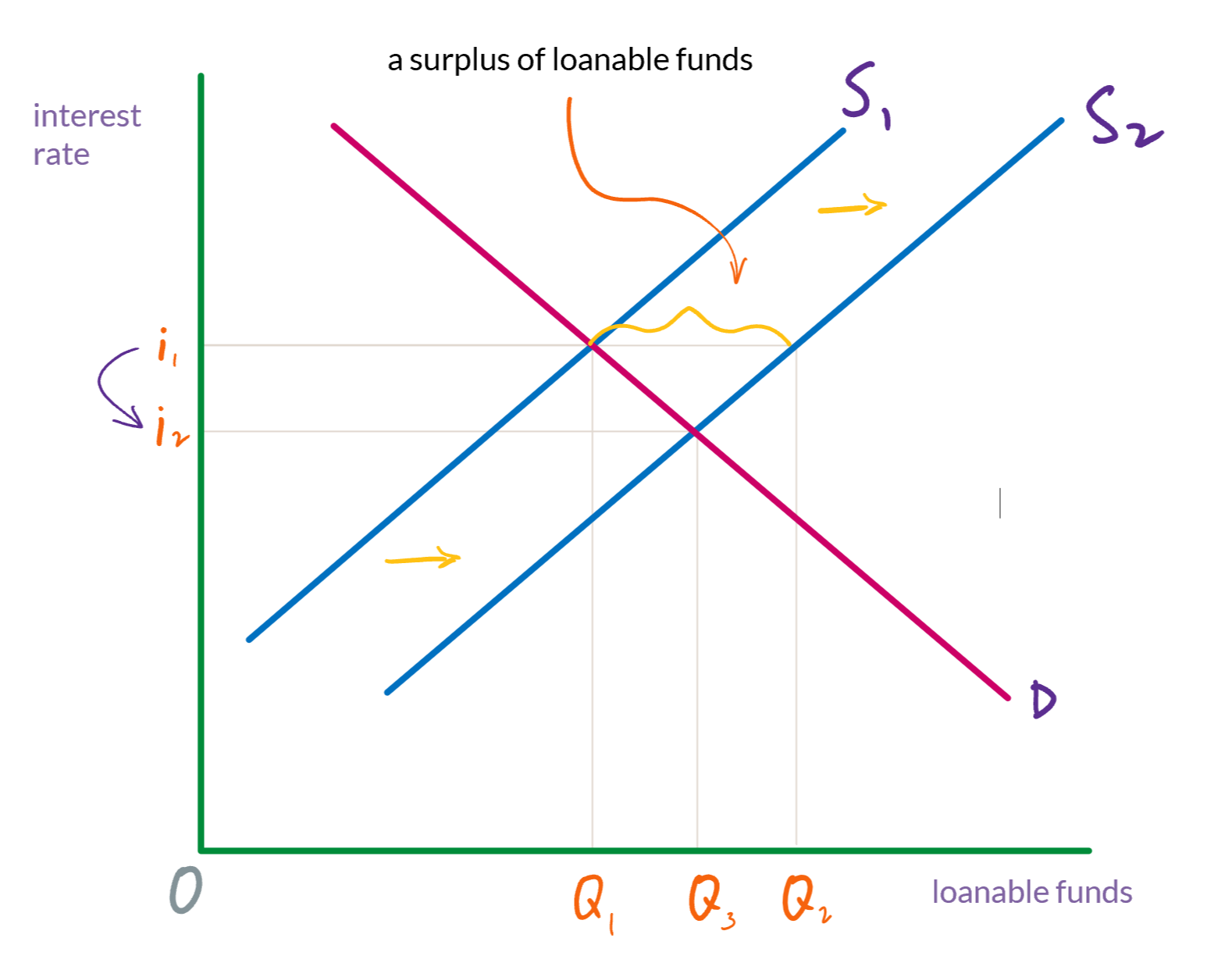

As you know, an increase to the the supply of loanable funds is represented by the supply curve shifting to the right. If interest rates don’t fall, however, then the quantity of loanable funds demanded won’t change. In figure 1, the quantity demanded will remain at Q1. The supply of loanable funds, meanwhile, will increase to Q3. Hence, there will be a surplus.

This surplus will drive the interest rate down until it reaches i2 where the quantity of loanable funds demanded equals the quantity supplied (Q3).

Before the supply of loanable funds increased (i.e., before the reserve requirement was changed), the amount of loans was Q1. Now, it is Q3. So, loans (i.e., borrowing) has increased.

Open market operations and loans

As we have seen, when the Federal Reserve buys or sells bonds, the bank’s will end up with either too much or too little held in reserve. The bank will get back to holding 10% of its deposits in reserve (or whatever the reserve requirement happens to be). It won’t, however, have the loan amount that we derive from the money multiplier formula.

In this situation, when the bank gets back to holding exactly the reserve requirement, its loans will be this amount:

\[\mathsf{maximum\ loans = \ \Bigl(\Bigl(\frac{1}{reserve\ requirement} \times reserves\Bigr)\ - reserves\Bigr)\ \pm the\ change\ to\ reserves}\]Change to reserves is the amount by which reserves changed when the bank bought or sold the bonds. Reserves is the amount that the bank has in reserve after that change. So, in our example of the Fed selling bonds to the bank, loans will only reach $7,000.

\[\mathsf{\Bigl(\Bigl(\frac{1}{.10} \times 800\Bigr)\ - 800\Bigr)\ - 200 = $7,000}\]To simplify matters, however, we can just calculate the amount of loans that the bank will have this way:

\[\mathsf{maximum\ loans = \ \Bigl(\frac{1}{reserve\ requirement} \times reserves\Bigr)\ - reserves}\]which in our example gave us this:

\[\mathsf{\Bigl(\frac{1}{.10} \times 800\Bigr)\ - 800 = $7,200}\]